Know Thy Place Director Damian Shiels recently took the opportunity to explore some of the archaeology of the place where he grew up, near the village of Ardagh, Co. Limerick. The area is extremely rich in later prehistoric and early medieval heritage, and was the find spot of one of the most famous artefacts ever discovered on the island of Ireland.

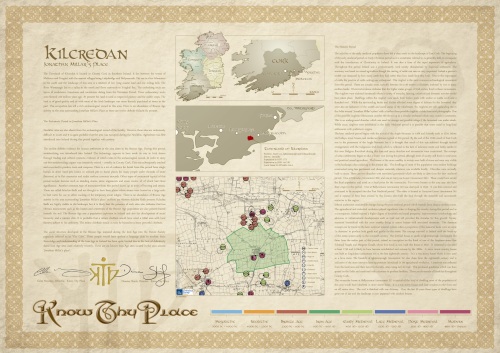

I was very fortunate to have an ‘archaeological view’ when I was growing up in Co. Limerick. Directly across from our front door it is possible to take in c. 2,000 years of history in a single glance. The first monument to catch your eye is the impressive banks and ditches of an early medieval ringfort, one of the many such homesteads that are dotted around the area. The view is dominated by the ‘Black Hill’, which overlooks this part of Limerick and from which you can see five counties (Limerick, Clare, Tipperary, Cork and Kerry). In 1981 analysis of an aerial photograph revealed banks and ditches surrounding the summit- the tell-tale signs of a hillfort, most probably dating to the Late Bronze Age some 3,000 years ago. The inner enclosure covers some 7.5 ha (18.5 acres) while the outer enclosure demarcates a huge 20.5 ha (50.5 acres), making this one of the largest known hillforts in Ireland.

The 'view across the road': Early Medieval Ringfort in The Commons, Ardagh, with the probable Late Bronze Age Hillfort of Ballylin, 'The Black Hill', in the background

While the ringfort and hillfort were a constant sight, neither was in the same townland as our house. My claim to fame growing up was that for many years our home was the only one in the townland of Reerasta South, the site of another ringfort. I have often visited the monument; today the banks and ditches on the western and eastern sides of the fort have been ploughed away, but those on the northern and southern side still stand to an impressive height.

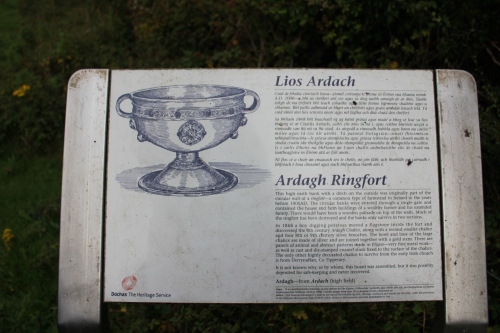

It may seem slightly odd to have once proudly proclaimed that ‘we are the only house in Reerasta South’ (and on reflection it was…), but, you see, Reerasta South had a claim to fame. One of the most notable events in the history of this part of rural Ireland took place here in 1868, when two youngsters, Paddy Flanagan and Jimmy Quin, were digging up potatoes in the ringfort. As they laboured away one of their spades struck what seemed to be a metallic object. Clearing away the soil to see what the obstruction was they discovered a small bronze chalice, which was clearly of significant antiquity. The boys wondered what else might be found, and continued the search. One can imagine their excitement as four silver-gilt brooches emerged from amongst the crop. However none of these objects were the star find- that was apparent at the moment of its discovery. Flanagan and Quin found a second chalice, this one made of precious metal and with some of the most exquisite decoration ever seen on an Irish object. This remarkable find has since become known as the ‘Ardagh Chalice’.

The Ardagh Hoard with the two chalices and four brooches. The stem of the smaller chalice was damaged when it was struck by a spade during its discovery in 1868

The two chalices are of 8th century date, while the brooches were manufactured sometime in the 9th century. It is possible that the objects were hidden during a Viking raid in the 9th or 10th century,with the individual who concealed them never returning to dig them up. The Ardagh Chalice is what is known as a calices ministeriales, a chalice used for giving wine to the faithful during mass. It is made up of hundreds of components and is heavily ornamented, using glass studs, silver inlays, gold filigree, a conical crystal and fabulous interlace and curvilinear designs. The main body is of silver, and the names of the apostles are inscribed on a band beneath the bowl. It is a unique masterpiece and represents the pinnacle of what could be achieved by early medieval Irish metalworking craftsmen.

Looking north from the interior of Reerasta Ringfort, with the 'Black Hill' Hillfort in the background. The hoard is thought to have been discovered in the western part of the fort

One wonders on each visit as to the circumstances of the deposition of these amazing artefacts, and why the people who hid them never returned to claim their property. Equally thoughts turn to the two boys who in 1868 after the passage of almost 1,000 years brought these objects to light. They did not gain from their find; Paddy Flanagan was later buried in a pauper’s grave in nearby Newcastle West, while Jimmy Quin had to emigrate to Australia to try to build a life.

The Ardagh Chalice itself was bought by the Bishop of Limerick who in turn sold it to the Royal Irish Academy. It is now on display in the National Museum of Ireland, where it is one of the treasures of the collection. Virtually every Irish person is familiar with the style of the chalice, even if they have never seen it in person. Every year the winners of the G.A.A. All-Ireland Senior Football Championship take home the Sam Maguire cup, which is modelled on the Ardagh Chalice and was first presented to the All Ireland Champions (Kildare) in 1928. Unfortunately the Sam Maguire has yet to return to its true ‘home’ in Co. Limerick, as the county last won the Championship in 1896…still, there is always hope for 2012!